A Celebration of Black History in the Outdoors

Outdoor Afro, the nation’s leading, cutting-edge network that celebrates and inspires Black connections and leadership in nature, has highlighted notable Black historical figures, places, and recent achievements of Black people related to outdoor recreation. We encourage you to follow @outdoorafro on Instagram and read through the entire series.

Matthew Henson

Matthew Henson was born in Maryland in 1866, the son of free sharecroppers. He was orphaned at the age of 7 or 8. Henson found work as a cabin boy and seaman and did so for several years before being hired as a valet on one of Peary’s survey expeditions. This began a decades-long working relationship with Peary. Henson’s skills were unmatched, and he made a total of seven voyages to the Arctic with Peary. On April 6, 1909, Henson became the first person to set foot on the North Pole. Four Inuit (Indigenous people of northern Canada), whose names were Egingwah, Ootah, Ooqueah, and Seegloo, assisted Peary and Henson.

Charles M. Crenchaw

In 1964, Charles Madison Crenchaw became the first Black man to reach the summit of Mount McKinley, also known as Denali, the highest peak in North America. During World War II Crenchaw served as a master sergeant in the U.S. Army Air Corps. As a flight engineer, he was in charge of maintenance for a squadron of airplanes flown by the Tuskegee Airmen.

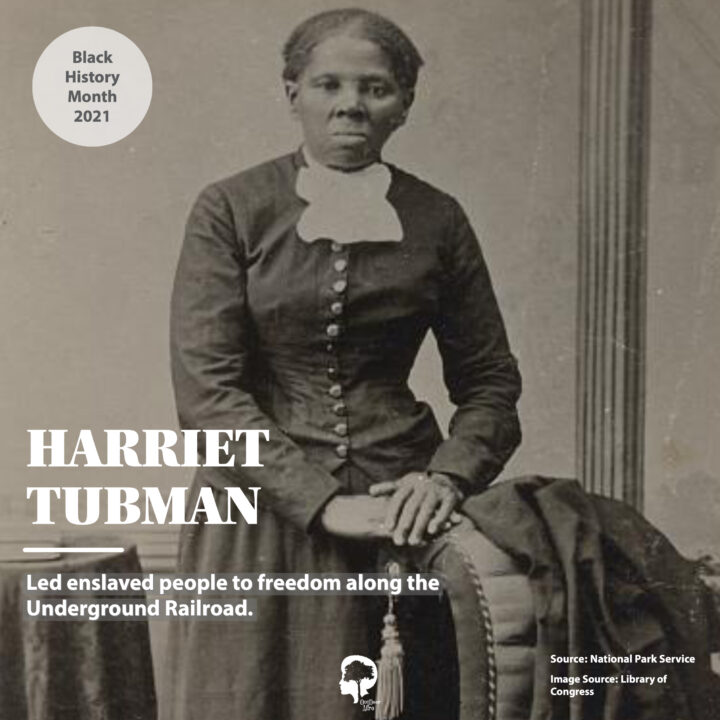

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman was known as a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, abolitionist, nurse, and Union spy. After escaping slavery herself in 1849, Tubman spent 10 years making approximately 13 trips to Maryland to rescue her family. She repeatedly risked her life to guide nearly 70 enslaved people north to freedom. In 1863, Tubman joined Col. James Montgomery and the 2nd South Carolina Infantry Regiment, comprised of emancipated slaves, in a raid on several plantations along the Combahee River. That raid led to the rescue of more than 700 enslaved people.

Outdoor Afro often reflects on Tubman’s relationship with nature and refers to her as “The Original” Outdoor Afro. She used the skills she learned while working on the wharves, fields, and woods, observing the stars and natural environment to lead people to freedom. Tubman also used her knowledge of plants, learned from her mother, to tend to the sick.

George W. Gibbs, Jr.

George Washington Gibbs, Jr. was born on November 7, 1916, in Jacksonville, Florida. Gibbs enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1935. Four years later, he was chosen from hundreds of applicants to join an expedition with the United States Antarctic Service (USAS). Their ship, the USS Bear, reached Antarctica on the morning of January 14, 1940. Gibbs recorded in his journal, “When the Bear came up to the ice close enough for me to get ashore, I was the first man aboard the ship to set foot on Little America and help tie her lines deep into the snow.” Gibbs retired from the Navy in 1959 as a chief petty officer and earned numerous medals of merit. He earned a degree from the University of Minnesota and was heavily involved in the community of Rochester, where he lived. Gibbs passed away on November 7, 2009.

The community of Rochester has since honored Gibbs by naming a school, street, and scholarship in his name. In 2009, the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names also recognized Gibbs’ accomplishments by naming a rock point on Horseshoe Island off the Antarctic Peninsula after him — Gibbs Point.

James P. Beckwourth

James Pierson Beckwourth was born into slavery in Virginia in 1798. After being freed, he began his life of trading and Western exploration. Beckwourth is acknowledged as the greatest Black frontiersman in the history of the American West. He is one of seven people credited with establishing the town of Pueblo, Colorado, and a low-elevation pass through the Sierra Nevada Mountains, which was named for him.

Acknowledgment

In 1829, Beckwourth began living among the Crow Tribe. He learned their language and customs and is said to have been deemed an honorary chief. Beckwourth led the Crow in a battle against the Blackfeet in 1831. In the mid-1830s, Beckwourth left his life with the Crow and joined the Missouri volunteer military force as a scout and interpreter, in which he was involved in the Seminole War in Florida. Beckwourth left the army around 1840 and spent the next decade wandering around the West, trading regularly with the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux peoples. He acted as a prominent go-between for indigenous peoples and the U.S. government along the Santa Fe Trail, as well as for Mexican traders on the Old Spanish Trail. Beckwourth eventually settled near Denver, Colorado, and continued to work periodically as a civilian scout for military parties. While serving as a scout for the Colorado Volunteers, he was involved in an expedition that resulted in the Sand Creek massacre in 1864.

How much Beckwourth knew about or participated in the inexcusable massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people is still disputed. There are accounts that state Beckwourth was unaware of plans for an attack and was outraged when it began. However, others consider Beckwourth a key participant. He eventually returned to live among the Crow, where he died in 1866.

Bessie Stringfield

Bessie Stringfield took eight long distance, solo rides around the United States in the 1930s and 1940s. During World War II, she worked for the army as a civilian motorcycle dispatch rider. The only woman in her unit and riding her own blue Harley Davidson, she carried mail and documents between domestic bases. In the 1950s Stringfield moved to Miami, Florida where locals nicknamed her “motorcycle queen of Miami.” Stringfield, who owned 27 motorcycles over her lifetime, passed away in 1993.

Stringfield was inducted into the American Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 2002. Today, pioneering female riders are recognized by the American Motorcyclist Association with the Bessie Stringfield Award.

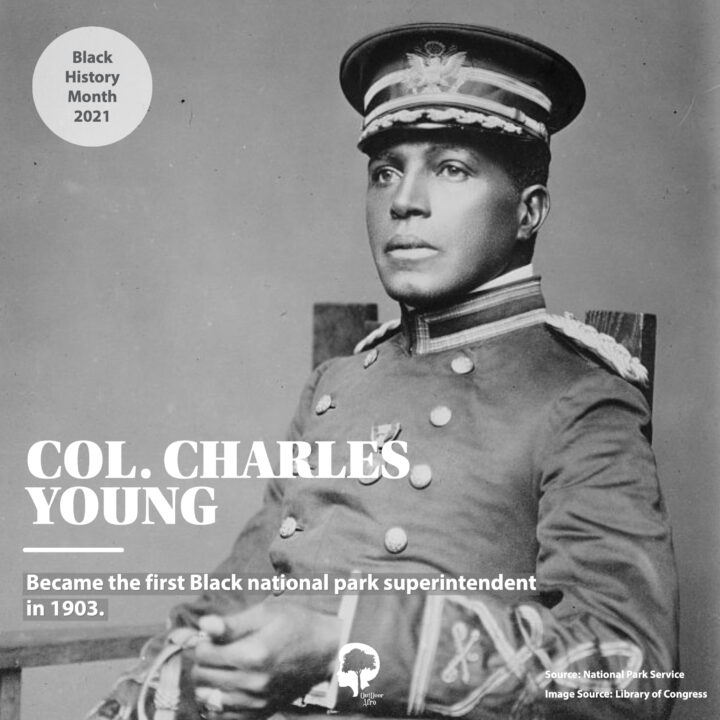

Col. Charles Young

In 1903, while serving as captain of a Black army company at the Presidio, a military post in San Francisco, Charles Young was asked to take his troops to Sequoia and General Grant national parks. He was appointed acting superintendent, making him the first Black superintendent of a national park. That summer, Young and his troops made more progress constructing roads and trails than any other troops before them. He went on to lead a long and distinguished military career.

MaVynee Betsch

Born in Jacksonville, Florida on January 13, 1935, MaVynee Betsch was the great-granddaughter of Abraham Lincoln-Lewis, who founded American Beach on Florida’s Amelia Island. After earning a degree from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio, Betsch moved to Europe, where she was an opera singer for 10 years.

After returning to Florida in the 1970s, she lived on the beach and dedicated the rest of her life to preserving and protecting the historic beach community and educating visitors. She donated her life savings of $750,000 to 60 environmental organizations and causes, 10 of which she was a lifetime member. She was the driving force behind the creation of a museum and collected historical artifacts herself. Betsch passed away on September 5, 2005 at age 70 after a battle with cancer. American Beach Museum opened its doors on September 6, 2014, bringing the lifelong dream of MaVynee Betsch to fruition.

Share:

2020 Gift Guide for Outdoor Lovers

Classes in Hammocks: Take Virtual Learning to the Next Level