Written by Greg Hlavaty

How this North Carolina university embraced hammocking as a form of connection and relaxation during unprecedented times.

Most teachers will tell you: pandemic teaching has been tough. Disengaged students, poor attendances, silent classes.

This past November, I was sleeping poorly and obsessing over why my writing classes at Elon University had never gelled. I’ve been teaching for 14 years, and my bag of teaching tricks is deep, but this semester, most of my efforts had failed.

During Thanksgiving Break, I made an odd decision: stop working so hard and just relax.

When campus emptied, I decided to play student for a day and set up my ENO hammock in one of Elon’s hammock stations. Erected in 2020 to help students socialize safely during Covid, these stations are a permanent set of metal poles that hold up to six hammocks in a star configuration.

With minimal setup, I clipped into the hammock station’s metal rings and sat down to scan the campus. With my back to the lake, I watched my kids bike around the deserted campus, explore the brick pathways, and wave when they passed.

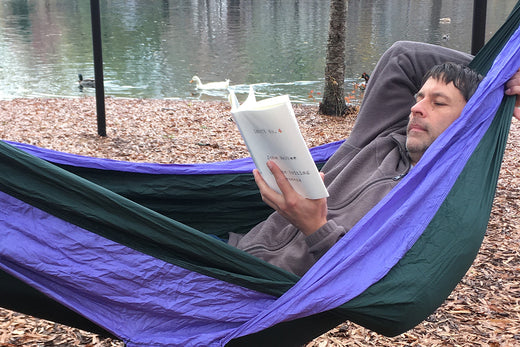

It felt strange to sit alone, so clearly unproductive, but I relaxed into the emptiness and lay back in the hammock.

Closing my eyes, I focused on the sound of the fountains, their spray hitting the water and lulling me. Although I’d told myself I’d bring some grading—I teach English, so the grading is endless—I ignored that directive and decided to read.

The best part? The reading was not required.

“Bye, Professor. We’re Going ENO-ing after Class!”

Last year, some students told me they were going “ENO-ing.”

I had a hammock. But ENO-ing?

To me, my hammock was a tool for camping, but to them, the ENO Hammock had become the sole activity.

I required travel to justify its use. My students? It’s part of their daily routine.

The brand had become a verb.

Which could be why the ENO hammock has become a staple of many college campuses. Walk through Elon University’s campus on a nice day and you’ll see hammocks strung in stations as well as under Magnolia trees.

A prime example: Genevieve Emerson, a senior majoring in Outdoor Leadership and Strategic Communications, sees her hammock as multi-functional. She camps in places like Pisgah National Forest and in Colorado, but on campus, she also uses her hammock to “study and just get outdoors.”

And while Emerson sees students hammocking with laptops to study, she believes that hammock stations have turned hammocking into “much more of a social activity.”

Socializing was the purpose of hammock stations, but Emerson believes the real appeal is the design of the ENO DoubleNest Hammock. Slightly wider hammocks allow people to sit in a hammock together, reinforcing the social angle.

As a parent, hammocking alone was my preference.

For once, I had no questions to answer, no laundry to fold.

Mental Health Benefits of Hammocking

As I hammocked that morning, I let sounds drift over me without focus: geese cackling, crows cawing, distant traffic passing. After just a few minutes of sensory awareness, I could feel the semester’s stress ebb, and I began to wonder why I didn’t do this more often.

Elon has a beautiful campus, and yet I often rush between buildings. Why not slow down and appreciate the green?

And why do we worry so much about performance? About things we cannot control?

Later, I asked Emerson, a Trip Leader at Elon Outdoors, why hammocking seems to stoke these mental health benefits. She said “it’s an intentional way to get outside because you do have to set [the hammock] up,” and you have to pay attention to your surroundings.

Trees you once ignored now command attention: Are they safe for hammocking? Are there weak limbs above that could fall? These questions can only be answered in the present moment.

Sure, clipping into the hammocking station was simple, but as I committed to the activity, I looked–really looked–at surroundings I once took for granted. Where was the best view? Would the wind be in my face? Would the oaks provide enough shade?

Wherever we set up, hammocking forces us to slow down and rewards attention. For me, I discovered a more relaxed mindset, one that I had forgotten could exist on campus, and I began to wonder about intention. How important our attitudes can be when facing challenge. How we define what matters.

Maybe, whether student or faculty, your intention can be simple: take care of yourself.

If you want to be with friends or to quietly connect with nature, you only need to make the time.

The space has already been made.

Author Bio

Greg Hlavaty, Senior Lecturer in English at Elon University, writes about outdoor adventure and nature awareness. For more information on his writing or coaching services, visit his website at www.fastwritingfeedback.com.

Share:

Get to Know the Artist Behind ENO's Newest DoubleNest® Print Hammock, Nature Talk

3 Outdoor Date Ideas With Your ENO Gear